A River’s Memory - The Life of Salmon

Every now and then, I’m reminded that the River Teign has a better long-term memory than I do. While I’m still trying to remember where I left my car keys, the Atlantic salmon are quietly navigating a four-year epic - from egg to ocean and back again - precisely, instinctively, without so much as a map or a WhatsApp group to stay in touch.

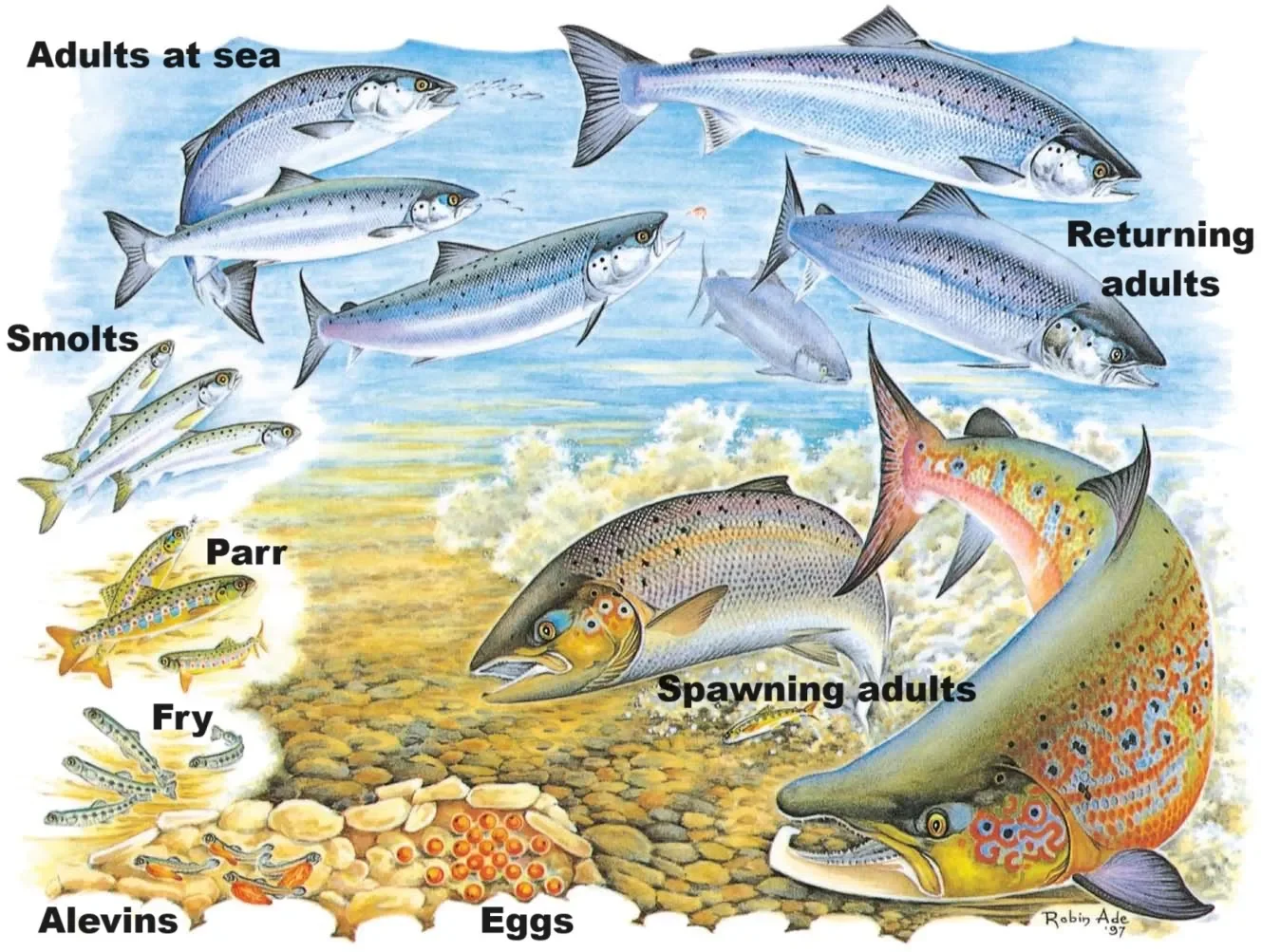

We often get asked about the different life stages of the Atlantic salmon - how long each phase lasts, how many survive, and why on earth so few adults are returning to UK rivers. So it felt like the right moment to put everything in one place for you all, using this brilliant illustration from the Atlantic Salmon Trust to guide us:

And yes, it’s a long story. And yes, it’s a miracle that any of them make it. And yes, it is exactly why we plan our work with the bigger picture in mind. So, let’s begin at the beginning and put some numbers to this amazing timeline…

1. Eggs - Thousands to Hundreds

(Late November–January)

A hen salmon will lay 1,000–1,500 eggs per kilogram of body weight. So a 6lb fish (similar to the ones seen at Drogo this year, around 2.7kg) may lay over 3,000 eggs. The male fertilises them, they settle into the redd, and… well… nature takes over.

But here’s a stark fact - Only 5–10% of those eggs actually survive to hatching. This can be due to floods washing them out. Sediment can suffocate them. Trout, birds and even other salmon will happily eat them. And then there’s water temperature… Above the dreaded 12 °C threshold sees high mortality and deformation.

So, from around 3,000 eggs, we may get 200–400 alevins.

This is where clean, oxygenated gravels - the kind we work hard to protect - makes all the difference.

2. Alevins - Hidden & Vulnerable

(February–March)

Once hatched, alevins stay buried in the gravel for several weeks, living off their yolk sac. They are essentially tiny, blinking ‘do not disturb’ signs.

A single badly-timed spate or a load of silt washing in from an eroded bank can easily wipe out a whole redd and these vulnerable young.

This is why bank repair, sediment reduction, and stable flow matter long before we even see fish.

3. Fry - Tiny, Hungry & Mostly Edible

(March–July)

When alevins finally emerge as fry, they enter a world similar to the drunken reveller emerging from a dark basement nightclub - where everything is seen as food… or a potential fight!

Survival from fry to parr is typically - 10–30%

That means from our original 3,000 eggs, we might now have - 20–120 fry

Development through this stage depends on good refuge - woody debris, shallow riffles, dappled shade - exactly the kind of features TACA works hard to restore. The Electro-fishing surveys carried out give us good indicators of population density during this stage and helps guide habitat and areas we should be improving or protecting.

4. Parr - The Striped Teenagers

(Year 1–3)

As a rule of thumb, Parr spend 1–3 years in the river (most Teign fish spend two). They defend tiny territories, feed on the river invertebrates, and rely on:

clean gravels,

stable flows,

and lots of hiding spots - Think woody debris!

A typical survival figure from parr onto the next stage is 15–40%

So, on from those 20–120 parr, we may see just - 3–40 smolts. And so the funnel narrows again!

5. Smolts - The Great Silver Migration

(April–May)

Smolts undergo one of nature’s great transformations: their bodies adapt for saltwater, their colour turns silver, and they begin their downstream migration.

Back in 2021 during the River Teign Restoration Project, a team released a large number of smolts from the Chagford Mill Stream Leat that had become trapped during a spate. They were all safely returned to the main river to continue their downstream journey to the sea, but only after we got to film them underwater first, of course!

Here’s another staggering statistic - Only 2–5% of smolts survive their time once they make it out to sea. With some UK rivers seeing returns as low as 1%.

I’ve said it and will say it again… You would have had a better chance of surviving the Battle of the Somme in 1916 than returning as a mature Atlantic Salmon.

So, from those 3–40 smolts… we realistically expect 1 to 2 adults back.

Suddenly, every returning fish feels like a miracle.

6. At Sea - 2,000 Miles of Danger

(Years 2–4)

Once they leave Teignmouth, most Teign salmon head north and west towards the feeding grounds around the Faroe Islands, Iceland and Greenland. During their time at sea, they pack on condition from feeding, but out there they face:

predators,

changing ocean temperatures,

declining food sources,

bycatch from industrial fisheries,

And great Atlantic storms you and I wouldn’t last a minute in!

This part of their journey is beyond our control, but the river they leave and return to is not.

7. Returning Adults - The Homeward Miracle

(Autumn, Year 4)

Most Teign salmon are four-year fish, meaning many of the strong, healthy fish we’ve seen leaping Drogo Weir this year may well be some of that Class of 2021 returning home.

Think about that for a moment: smolts we helped slip back into the Teign as silver youngsters are now fighting their way back through the same system as mature adults. So they’ve endured four winters, thousands of miles. And they still find their home by smell alone. Honestly, these resilient fish never stop defying the odds!

8. Spawning Adults - And so the Cycle Begins Again

At the end of their journey, the salmon excavate redds in clean gravel, lay their eggs, and begin the cycle all over again. Their job is done, and the river takes over.

And that’s exactly the moment we are entering now - redd-spotting season - where every clean patch of freshly turned gravel serves as a quiet victory.

Final Thoughts

Once you read these numbers:

3,000 eggs → 200 alevins → 20 fry → 20 parr → 3–40 smolts → 0–2 adults.

The fragility of the Atlantic Salmon becomes crystal clear.

And so does the power of local action and outcomes. We alone can’t influence the Greenland Sea. We can’t alone control ocean temperatures. But we can improve every metre of habitat between the headwaters and Teignmouth. And from what we’ve seen… when we get involved and do what we can to improve habitat and migration, the fish respond.

Everything we do today shapes the salmon we will see again in 2028, 2029 and 2030. And everything we did in 2021? I like to think that we’re seeing the results right now.

So next time you’re standing by a river watching a salmon leap, remember the odds it overcame to get there. Remember the gravel bed it came from. And remember that the work we do today together is shaping the fish that will return four winters from now. Because if we give them a river that works, I know they’ll do the rest.